What I talk about when I talk about swimming

I learned to swim at 27. But I’m not talking about swimming as in keeping my body afloat for the first time, mastering the movement of holding my head bobbing over water, pushing and thrusting with my feet—and subsequently not drowning. My older sister learned me that (like she did with most things, bike riding and mischief included) at six at this alpine ski resort pool in the middle of Norway. I was a stick figure girl and very short for my age.

I remember the pool being completely incased in glass and that the snow was eerily bright outside. It was equally as claustrophobic as it was beautiful and I mastered a few weak strokes before my sister yelled out in glee.

I have few other memories from the affair itself, apart from obviously not being afraid of drowning ever again—and that I found a nice book about birds in the gift shop of the resort that I convinced my mom we should buy for my grandmother, because she liked birds. My mother silently complied. And I could swim. Or at least I thought I could. Because a few years back I got an urge to learn how to swim properly. I’m talking about actually mastering water and working with it, not against it. And then I realized that learning to swim, again, is indeed a fight for your life.

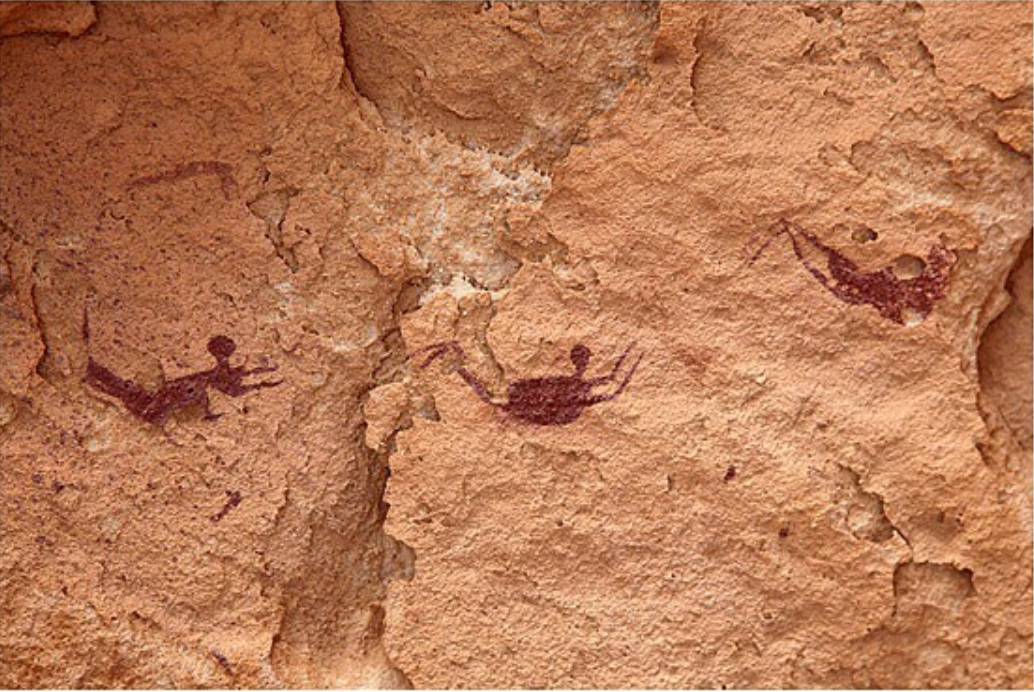

It’s quite crazy, but the first cave paintings depicting the act of swimming dates back 10,000 years and were found in the Cave of Swimmers, near Wadi Sura in southwestern Egypt.

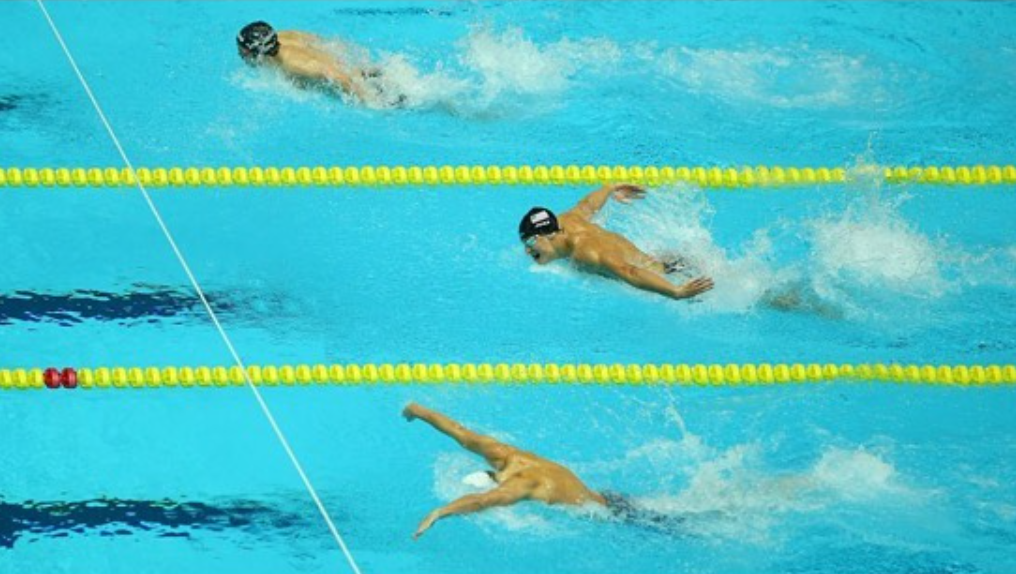

The kind of frog swimming or dog paddle most of humans do today is a rather primitive way of moving through water. We call it breaststroke, but it’s not an actual breaststroke either (search for competitive breaststroke on YouTube and YOU’LL KNOW WHAT I MEAN), as proper breaststroke is done halfway under water, your whole body submerged as you stretch out as an arrow and take a full stroke, before bobbing your head quickly up for air.

In terms of efficiency, the front crawl—where your head is submerged at all times, moving sideways for air as your arms stretch over your head, plunging through the water and pulling you forward like a windmill, feet in a mermaid kick position like a fish—is far superior, but that’s not the only reason why I wanted to learn this movement. I found breaststroke clunky, and it felt unnatural in some way treading water in a semi-upright position. If your local swimming pool has one of those «blue eyes» I recommend you watch swimmers from below, you’ll easily separate the frogs from the fish.

I had my first front crawl swimming lessons with eight other adults in the university pool in Oslo. Three were three awkward looking men who wanted to try triathlon (SHOCKER), the other five were women. We were a big splashy mess and quickly entered survival mode. I literally ate, chew and spat chlorine for the next few weeks. I don’t know how many ounces of water I mush have swallowed, but I remembered feeling bloated and light-headed after every session, unsure if I would ever get the rhythm of breathing and coordination of hands and feet down. I felt like I was literally drowning at all times, and we all had moments of sheer desperation: doing a full stop mid-pool, heads up, gasping for air, arms flailing.

And the smell, the smell of chlorine, it followed me everywhere, even though I scrubbed my skin red after every practice.